Those of you who stayed up late to hear Anthony Albanese’s victory speech on election night would have noted that his opening line was to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land where he stood, and promise that Labor will commit “in full” to the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

For most Australians, the Statement from the Heart will be about as familiar as Appendix 23 in the Budget papers. You’re more likely to know the lyrics of Waltzing Matilda, even though it was released five years ago.

That a majority of Australians would not be able to recall even a few words of this gracious document or understand what it means, is an indictment on a political era that has functioned on fear.

Changing that ignorance and achieving a positive referendum result will be a monumental communications exercise for the new Government.

The most recent polling conducted by the Guardian suggests that more than half the sample — 52 per cent — now support a treaty with Indigenous Australians. This is a five-point increase from 2017, when the question was last asked.

53 per cent of respondents also supported a constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament in line with the Uluru statement, an eight-point increase since 2017.

Even though half of us support the idea of constitutional recognition, many of us still feel helpless about how to achieve it.

As we reach the end of National Reconciliation Week 2022, a first step might be to familiarise ourselves with the text.

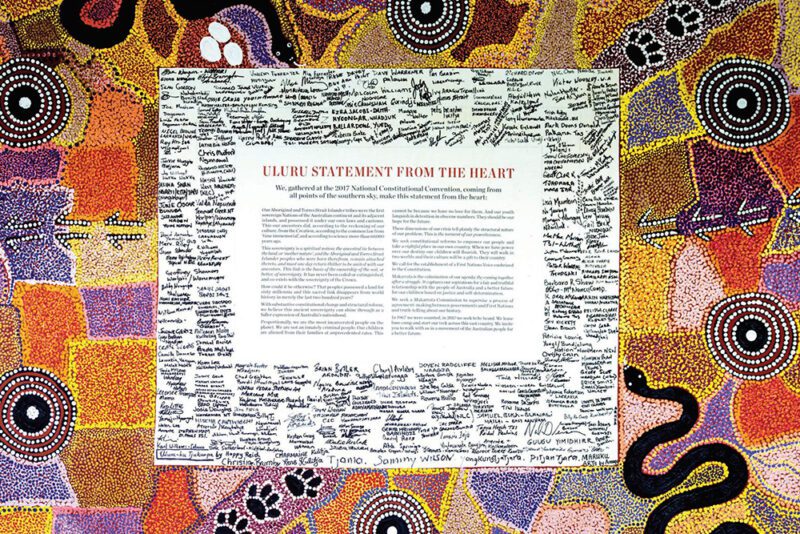

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

How could it be otherwise? That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years?

With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are alienated from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country. When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country.

We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history.

In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard. We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

The new Labor government has essentially adopted a staged approach to change.

Firstly a First Nations voice to parliament, a forum through which First Nations can advocate to the parliament and government. This voice will be enshrined in the constitution, so it cannot be removed by any current or future government.

The Government hopes that the referendum will be held in 2024.

Secondly, the statement calls for a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making. “Makarrata” is a Yolngu word that means to make peace.

Built into the Makarrata Commision will be the third stage: truth telling.

The details of this final stage remain unclear, but it is expected that the commission would be unbiased and open in uncovering injustices experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, much as the inquiry into the stolen generation in the late 1990s did.

The communication challenges

While the Statement is not exactly a call to revolution, Australia has been incredibly slow to deliver constitutional rights to Indigenous people.

It’s more than a century since South Australia became the first electorate in the world to give equal political rights to both women and men, including Indigenous men and women.

However, it took until 1962 for the The Commonwealth Electoral Act to grant all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people the option to enrol and vote in federal elections — but enrollment was not compulsory. It was not until 1984 (almost a century after the SA law change) that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people gained full equality with other electors under the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 1983. This Act made enrolling to vote at federal elections compulsory for Indigenous Australians.

The last indigenous-issue referendum was in 1967 when Australians voted overwhelmingly to amend the Constitution to allow the Commonwealth to make laws for Aboriginal people and include them in the census. That was so unanimous (91 per cent) that a ‘No’ case was not even developed.

But that history of success is not typical of referendums in Australia.

As constitutional lawyer Greg Craven wrote in The Weekend Australian: “The Australian people are by disposition constitutionally cautious. They know they have a pretty good Constitution, so they will not change if they perceive the least danger.”

Craven argues that this referendum will “not be about good media and attractive packaging.”

“As many opinion leaders as possible – plus some more – need to be in favour of the voice.”

He is nevertheless optimistic based on the move by the nation’s religious leaders — from Catholics and Anglicans to Hindus and Moslems — to support the Statement immediately after the election.

“This unprecedented alliance shows….the voice is not a fringe issue promoted by Indigenous activists and their leftie allies. It has the considered support of a vast array of serious people concerned with serious issues,” he says.

Fuller Brand Communication is an apolitical agency that has never abused the trust of our staff or clients by taking party political sides in elections. We, like most other small businesses and corporations, don’t want this reflection on several hundred years of neglect, to be another unseemly political shouting match.

We want this to be a positive contribution to the healing of our country.

How the business community can be an example of leadership

Back in 2019, fourteen Australian organisations united for National Reconciliation Week to support the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

The ‘Response to the Uluru Statement’ was developed by BHP, Curtin University, Herbert Smith Freehills, IAG, KPMG, Lendlease, National Rugby League, PwC Australia, PwC’s Indigenous Consulting, Qantas, Richmond Football Club, Rio Tinto, Swinburne University of Technology and Woodside.

The response supported the call for a referendum to enable constitutional reform and encourage others to join in the national dialogue.

Sadly, it is not clear from my research if that Response is still valid or indeed if there have been other signatories.

However, one thing the organisations did have in common was a Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP).

Since 2006, Reconciliation Action Plans (RAPs) have enabled organisations to strategically take action to advance reconciliation.

RAPs are based on the core pillars of relationships, respect and opportunities, and they provide tangible and substantive benefits for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This includes employment opportunities, economic equity and support for self-determination.

RAPs assist businesses to embed the principles and purpose of reconciliation. The RAP network is a diverse group of more than 1,100 organisations that directly impact over three million Australians at work every day.

As a small business that is currently working our way through our own Reconciliation Action Plan, I can say that while the process is necessarily confronting and challenging it is also culturally unifying and enormously rewarding.

We have all learnt more about our unconscious biases and reflected on how our communications industry (and the media we often work in partnership with) have been part of the problem, but should now be part of the solution.

There are only a few times in our lives when we can make a real contribution to history that will be remembered by our grandchildren. This is one of those times.

For more information about how to support the Uluru Statement visit the Uluru Statement website.